Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15 Feb 2023

Automatic approach-avoidance tendency toward physical activity, sedentary, and neutral stimuli as a function of age, explicit affective attitude, and intention to be activeAta Farajzadeh, Miriam Goubran, Alexa Beehler, Noura Cherkawi, Paula Morrison, Margaux de Chanaleilles, Silvio Maltagliati, Boris Cheval, Matthew W. Miller, Lisa Sheehy, Martin Bilodeau, Dan Orsholits, Matthieu P. Boisgontier https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.05.22279509Relationship between age and physical and sedentary stimuli.Recommended by Florent Lebon based on reviews by Lilian Fautrelle and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Lilian Fautrelle and 1 anonymous reviewer

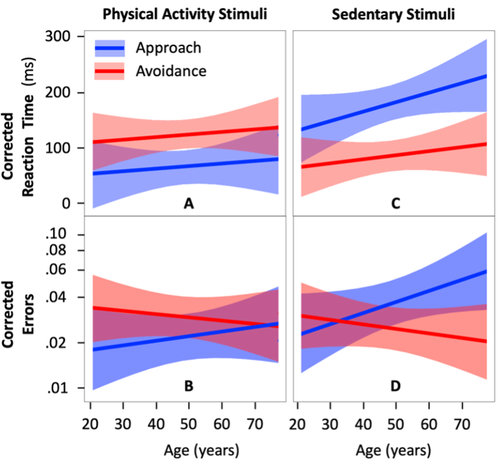

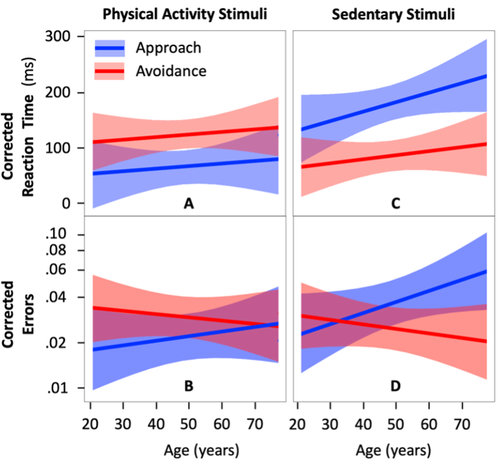

Up to now, the automatic approach-avoidance tendency towards physical activity and sedentary stimuli has been studied in various categories of the population. Previous studies showed faster reaction times (RTs) when approaching physical activity stimuli and avoiding sedentary stimuli, especially in healthy young individuals (Cheval et al., 2014; Locke & Berry, 2021). However, the whole spectrum of adulthood has never been tested within the same experiment. A first strength of the study of Farajzadeh et al. (2023) is that they constructed an online paradigm and analyzed the results of 130 participants aged between 21 and 77 years. It should be noted that this study has been pre-registered (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7GXZR). Overall the authors performed the experiment as first described. They updated their a priori power analysis, including the highest number of predictors (six tested predictors including two interaction effects and a total of eleven predictors). This increased the planned number of participants recruited from 85 to 144. Also, in addition to planned hypotheses, exploratory analyses were conducted to test whether automatic approach-avoidance tendencies toward physical activity and sedentary behaviors were associated with explicit attitudes and the intention to be physically active across aging. The authors recorded RTs and errors when participants had to approach/move an avatar towards/away from physical activity and sedentary stimuli. Another strength lies in data analysis and statistical design. To avoid any misinterpretation of the results, which could arise from an increase in RTs relative to age, the authors had the foresight to measure RTs when approaching/avoiding neutral stimuli (ellipses and rectangles). Taking into account such individuals differences, Farajzadeh et al. confirmed a main tendency to approach physical activity stimuli and to avoid sedentary stimuli throughout the lifespan. When the participants considered physical activity as the most pleasant and enjoyable (explicit affective attitude toward physical activity), the RTs were shorter when approaching physical activity and avoiding sedentary stimuli, irrespective of age. However, the intention to be physically active did not influence the individual's RTs. Altogether, the study by Farajzadeh et al. suggests that age and explicit attitudes modulate the time to respond to physical activity and sedentary stimuli. References Cheval, B., Sarrazin, P., and Pelletier, L. (2014). Impulsive approach tendencies toward physical activity and sedentary behaviors, but not reflective intentions, prospectively predict non-exercise activity thermogenesis. PLoS One, 9(12), e115238. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115238 Farajzadeh, A., Goubran, M., Beehler, A., Cherkawi, N., Morrison, P., de Chanaleilles, M., Maltagliati, S., Cheval, B., Miller, M.W., Sheehy, L., Bilodeau, M., Orsholits, D., and Boisgontier, M.P. (2023) Automatic approach-avoidance tendency toward physical activity, sedentary, and neutral stimuli as a function of age, explicit affective attitude, and intention to be active. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.05.22279509 Locke, S. R., and Berry, T. R. (2021). Examining the relationship between exercise-related cognitive errors, exercise schema, and implicit associations. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 43(4), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2021-0031 | Automatic approach-avoidance tendency toward physical activity, sedentary, and neutral stimuli as a function of age, explicit affective attitude, and intention to be active | Ata Farajzadeh, Miriam Goubran, Alexa Beehler, Noura Cherkawi, Paula Morrison, Margaux de Chanaleilles, Silvio Maltagliati, Boris Cheval, Matthew W. Miller, Lisa Sheehy, Martin Bilodeau, Dan Orsholits, Matthieu P. Boisgontier | <p>Using computerized reaction-time tasks assessing automatic attitudes, studies have shown that healthy young adults have faster reaction times when approaching physical activity stimuli than when avoiding them. The opposite has been observed for... |  | Behavioral/Cognitive Neuroscience, Humans | Florent Lebon | 2022-09-09 22:34:03 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

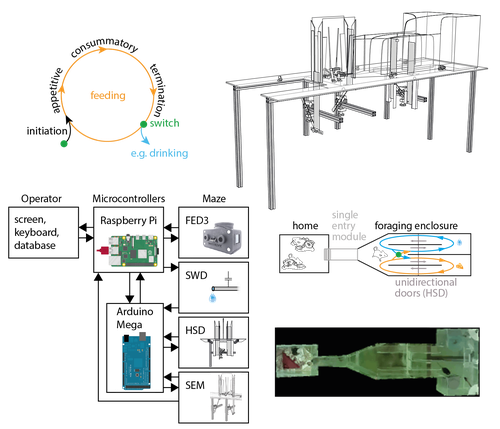

The Switchmaze: an open-design device for measuring motivation and drive switching in miceClara Hartmann, Ambika Mahajan, Vinicius Borges, Lotte Razenberg, Yves Thönnes, Mahesh M. Karnani https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.31.578188Novel automated training platform for studying flexible switching among natural motivated behaviors in miceRecommended by Balázs Hangya based on reviews by Ede Attila Rancz and Ewelina KnapskaAs our understanding of the building blocks of mammalian behavior improves, there is a shifting focus towards addressing the brain mechanisms of behavioral flexibility, strategy learning and behavioral switching (Banerjee et al., 2020; López-Yépez et al., 2021; Manzur et al., 2023). This requires novel behavioral paradigms and new tools: Hartmann and colleagues started filling this gap by presenting an open-source automated training system for studying motivational switching, which they coined the ‘Switchmaze’ (Hartmann et al., 2024). Instead of training mice on specific tasks, Hartmann et al. chose to quantify switching between spontaneous motivated behaviors like feeding, drinking, and engaging in social interactions in a type of foraging task. These behaviors were spatially separated by a smart design using distinct compartments with unidirectional doors, allowing the counting of discrete cycles of food and water intake in unitary quantities. Switching behavior was quantified by the ratio of shifting from one behavioral chamber to another (single probe entries) versus exploitation of a single chamber through multiple consecutive entries (continuous exploitation runs), termed ‘motivation switching rate’ (MSR). Interestingly, the measured MSR values were well within the distribution of randomized data in which the trial sequence was shuffled. The Authors suggest that this may be an adaptive strategy to decrease behavioral predictability and thus fool competitors and predators; however, determining the significance of this finding will require further testing. For instance, is a ‘more random mouse’ indeed more successful in a competitive setting where the total amounts of food and water are limited? Food deprivation increased, while re-feeding decreased switch rate, strengthening the arguments for the MSR being a strategically controlled parameter. Hartmann et al. further demonstrated the utility of the Switchmaze by performing chemogenetic inhibition of prefrontal cortical neurons projecting to the hypothalamus, a pathway thought to be involved in controlling feeding behavior (Petrovich et al., 2005; Cole et al., 2020; Padilla-Coreano et al., 2022). Mice showed an increased MSR upon inhibition, now significantly different from randomized distributions. Further analysis revealed that the difference was driven by a selective reduction of food-to-food transitions, that is, a decreased tendency for repetitive feeding. Moreover, this was due to a decrease in the number but not the duration of food runs, suggesting a specific behavioral role of the prefrontal-hypothalamic pathway in promoting repetitive feeding. In summary, Hartmann and colleagues showcased an affordable, open-source behavioral design and demonstrated its usefulness for quantifying flexible switching of natural behaviors. It is ideal for testing the effect of pharmacological and chemogenetic manipulations, but it can likely be combined with electrophysiology, fiber photometry or miniscope imaging, greatly broadening its potential. Therefore, the Switchmaze is a valuable member of the growing family of open source, automated rodent training tools (Puścian et al., 2016; Erskine et al., 2019; Qiao et al., 2019; Birtalan et al., 2020; Cano-Ferrer et al., 2024) that represent the logical next step for high-throughput, stress- and bias-free behavioral experimentation.

References Banerjee A, Parente G, Teutsch J, Lewis C, Voigt FF, Helmchen F (2020) Value-guided remapping of sensory cortex by lateral orbitofrontal cortex. Nature 585:245–250 Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2704-z. Birtalan E, Bánhidi A, Sanders JI, Balázsfi D, Hangya B (2020) Efficient training of mice on the 5-choice serial reaction time task in an automated rodent training system. Sci Rep 10:22362 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79290-2. Cano-Ferrer X, Tran-Van-Minh A, Rancz E (2024) RPM: An open-source Rotation Platform for open- and closed-loop vestibular stimulation in head-fixed Mice. J Neurosci Methods 401:110002 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2023.110002. Cole S, Keefer SE, Anderson LC, Petrovich GD (2020) Medial Prefrontal Cortex Neural Plasticity, Orexin Receptor 1 Signaling, and Connectivity with the Lateral Hypothalamus Are Necessary in Cue-Potentiated Feeding. J Neurosci 40:1744–1755 Available at: https://www.jneurosci.org/lookup/doi/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1803-19.2020. Erskine A, Bus T, Herb JT, Schaefer AT (2019) AutonoMouse: High throughput operant conditioning reveals progressive impairment with graded olfactory bulb lesions Reisert J, ed. PLoS One 14:e0211571 Available at: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211571. Hartmann C, Mahajan A, Borges V, Razenberg L, Thönnes Y, Karnani MM (2024) The Switchmaze: an open-design device for measuring motivation and drive switching in mice. bioRxiv:1–17 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.31.578188. López-Yépez JS, Martin J, Hulme O, Kvitsiani D (2021) Choice history effects in mice and humans improve reward harvesting efficiency Palminteri S, ed. PLOS Comput Biol 17:e1009452 Available at: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009452. Manzur HE, Vlasov K, Jhong Y-J, Chen H-Y, Lin S-C (2023) The behavioral signature of stepwise learning strategy in male rats and its neural correlate in the basal forebrain. Nat Commun 14:4415 Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-40145-9. Padilla-Coreano N et al. (2022) Cortical ensembles orchestrate social competition through hypothalamic outputs. Nature 603:667–671 Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04507-5. Petrovich GD, Holland PC, Gallagher M (2005) Amygdalar and Prefrontal Pathways to the Lateral Hypothalamus Are Activated by a Learned Cue That Stimulates Eating. J Neurosci 25:8295–8302 Available at: https://www.jneurosci.org/lookup/doi/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2480-05.2005. Puścian A, Łęski S, Kasprowicz G, Winiarski M, Borowska J, Nikolaev T, Boguszewski PM, Lipp H-P, Knapska E (2016) Eco-HAB as a fully automated and ecologically relevant assessment of social impairments in mouse models of autism. Elife 5:1–22 Available at: https://elifesciences.org/articles/19532. Qiao M, Zhang T, Segalin C, Sam S, Perona P, Meister M (2019) Mouse Academy: high-throughput automated training and trial-by-trial behavioral analysis during learning. bioRxiv:467878 Available at: http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2019/02/13/467878.abstract.

| The Switchmaze: an open-design device for measuring motivation and drive switching in mice | Clara Hartmann, Ambika Mahajan, Vinicius Borges, Lotte Razenberg, Yves Thönnes, Mahesh M. Karnani | <p>Animals need to switch between motivated behaviours, like drinking, feeding or social interaction, to meet environmental availability, internal needs and more complex ethological needs such as hiding future actions from competitors. Inflexible,... |  | Behavioral/Cognitive Neuroscience, Methods development, Rodent model system | Balázs Hangya | 2024-02-13 18:58:48 | View | |

12 Oct 2023

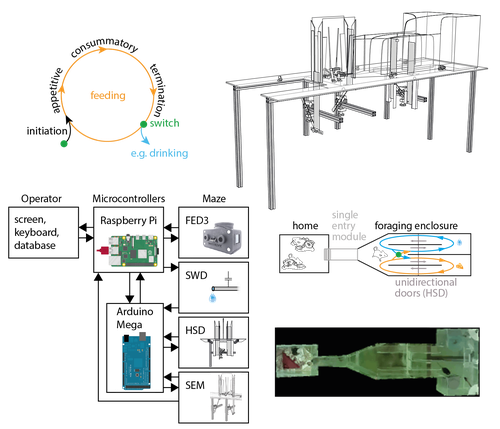

A meta-analysis of the effect of protein synthesis inhibitors on rodent fear conditioningClarissa F. D. Carneiro, Felippe E. Amorim, Olavo B. Amaral https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.11.509645Bridging consensus and controversy in fear conditioning research via meta-analysisRecommended by Sara Garofalo based on reviews by Emiliano Merlo and 1 anonymous reviewerThe study conducted by Carneiro and colleagues (Carneiro et al., 2023) seeks to explore the specific circumstances that influence the impact of protein synthesis inhibitors on the formation and endurance of fear-related memories. This investigation takes the form of a comprehensive meta-analysis of existing literature, making two significant contributions. Firstly, it enhances our understanding of fear conditioning by corroborating established interpretations (Schroyens et al., 2019, 2021) while also introducing novel insights. Secondly, it contributes to the ongoing discourse within behavioral neuroscience regarding the practicality and challenges of applying systematic reviews and meta-analyses to pre-clinical research (Prinz et al., 2011; Errington et al., 2021). To delve deeper into the subject, the authors conducted distinct meta-analyses for different injection sites and target sessions, thus examining the intervention's effects under varying conditions. Their findings highlight the robust influence of protein synthesis inhibitors on memory consolidation and reconsolidation, but suggest a lack of significant impact on extinction, potentially attributed to the limited number of studies on this topic. Notably, their analysis pinpoints certain well-recognized influencing factors, such as intervention timing and re-exposure duration. However, other proposed boundary conditions, such as memory age and training strength, do not appear to significantly influence the effect size, possibly due to a limited number of studies. This leads to the conclusion that while meta-analyses are valuable for consolidating existing knowledge, substantiation through well-powered, confirmatory experiments is imperative. Moreover, the research underlines the substantial heterogeneity among individual experiments, particularly within studies, which poses challenges for meta-analysis. Aggregating studies using various methodologies increases the capacity to identify influencing factors, emphasizing the importance of these approaches. The study also addresses the limitations of existing meta-analysis methods and suggests that additional sources of variability and difficulties in replication may exist, extending beyond the usual boundary conditions. These challenges could be attributed to biases within the literature, random error, or variations in experimental protocols. The paper highlights the significance of rigorous and reproducible research practices in pre-clinical investigations, emphasizing the need for an iterative process that combines data synthesis with empirical testing. While meta-analyses serve as valuable tools for knowledge consolidation, the authors stress that they cannot replace high-powered, confirmatory replication studies. Consequently, they advocate for a more holistic and interconnected approach to experimental science, incorporating data synthesis with empirical validation to enhance the reliability of research findings.

References Carneiro CFD, Amorim FE, Amaral OB (2023) A meta-analysis of the effect of protein synthesis inhibitors on rodent fear conditioning. , 2022.10.11.509645. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.11.509645 Errington TM, Mathur M, Soderberg CK, Denis A, Perfito N, Iorns E, Nosek BA (2021) Investigating the replicability of preclinical cancer biology. eLife, 10, e71601. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.71601 Prinz F, Schlange T, Asadullah K (2011) Believe it or not: how much can we rely on published data on potential drug targets? Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 10, 712. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3439-c1 Schroyens N, Alfei JM, Schnell AE, Luyten L, Beckers T (2019) Limited replicability of drug-induced amnesia after contextual fear memory retrieval in rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 166, 107105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2019.107105 Schroyens N, Sigwald EL, Van Den Noortgate W, Beckers T, Luyten L (2021) Reactivation-Dependent Amnesia for Contextual Fear Memories: Evidence for Publication Bias. eNeuro, 8, ENEURO.0108-20.2020. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0108-20.2020

| A meta-analysis of the effect of protein synthesis inhibitors on rodent fear conditioning | Clarissa F. D. Carneiro, Felippe E. Amorim, Olavo B. Amaral | <p>Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been increasingly recognized for their potential value in pre-clinical research, but their multiple applications have not been extensively explored in behavioral neuroscience. In this work, we studied p... |  | Behavioral/Cognitive Neuroscience | Sara Garofalo | 2023-04-03 16:20:41 | View | |

26 Jul 2022

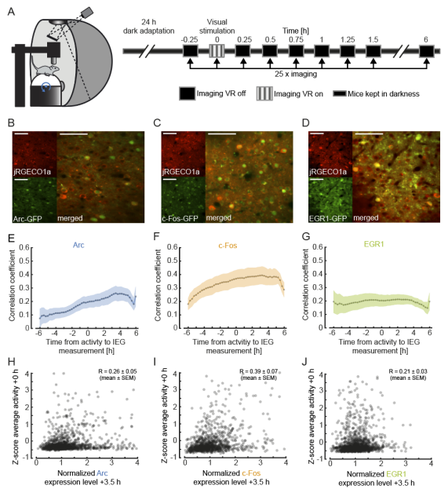

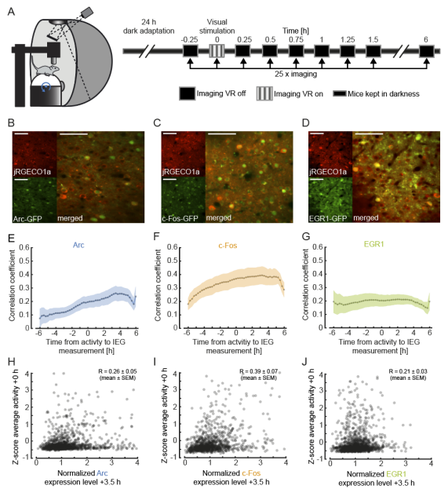

Functional correlates of immediate early gene expression in mouse visual cortexDavid Mahringer, Pawel Zmarz, Hiroyuki Okuno, Haruhiko Bito, Georg B. Keller https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.12.379909Bringing together immediate early genes and sensorimotor response properties in V1Recommended by Julia Jade Harris and Sepiedeh Keshavarzi based on reviews by Balázs Hangya and 2 anonymous reviewersThe primary visual cortex (V1) does not just process vision: it also integrates self-generated motion signals (Niell, Stryker 2010; Keller et al. 2012; Saleem et al. 2013; Vélez-Fort et al. 2018; Meyer et al. 2018), enabling us to match our actions to the world we see. We know that the development of visuomotor representation in V1 depends on experience (Attinger et al. 2017; Widmer et al. 2022), but how exactly does each neuron acquire the right balance of visual and motor input? And how do some neurons become more responsive to visual or motor signals? Mahringer et al. (Mahringer et al. 2022) suspected that the answers may lie in experience-specific plasticity mechanisms. To investigate this, the authors measured the expression of immediate early genes (IEGs) as indicators of both past neural activity and future plasticity. They examined three IEGs previously implicated in visual cortical plasticity: c-fos, egr1 and Arc (Yamada et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2006; Xie et al. 2014). In three separate transgenic mouse lines, GFP expression was driven by these IEGs, and a red variant of a genetically encoded calcium indicator allowed for simultaneous measurement of neuronal activity. Initial characterisation of IEG expression and calcium fluorescence revealed that IEG levels were only weakly (positively) correlated with visually-evoked neural activity. But what about the relationship between IEG expression and first visual or visuomotor experience? In dark-reared mice, first visual and visuomotor experiences led to differential IEG expression: Arc expression increased after first visual and visuomotor experiences; EGR1 expression decreased after first visuomotor experience; and c-Fos expression remained largely unchanged. Neural activity levels could not account for these changes, suggesting that different sensory experiences can selectively recruit different IEG expression patterns, perhaps according to input pathway. Further analysis of those neurons with the highest levels of IEG expression revealed that different IEGs were associated with different functional response properties. High Arc-expressing neurons developed above-average visual and below-average motor responses, while high EGR1-expressing neurons developed above-average motor responses. These results suggest that during experience-dependent wiring, Arc expression drives plasticity favouring bottom-up visual input, while EGR1 expression drives plasticity favouring top-down motor input. Interestingly, while Arc-expressing neurons appear to end up with little-to-no motor input, EGR1-expressing neurons appear to enjoy both visual and motor input, enabling them to display above-average visuomotor mismatch responses. Overall, this work makes two important advances. First, it suggests that IEG expression may be more closely linked to specific forms of plasticity than general levels of neural activity. Second, it reveals a mechanism by which visual cortical neurons can acquire specific functional properties by selectively upregulating bottom-up or top-down inputs in response to particular sensory experiences. As an additional note, we would like to highlight a vigorous technical discussion that this manuscript triggered: unconventionally, the authors chose not to apply a neuropil correction procedure to their calcium imaging data. This decision split opinion, amongst both reviewers and recommenders. We have come to the view that the findings are nevertheless of interest for the community and are pleased to point readers towards the publicly available reviews and authors’ responses.

Attinger A, Wang B, Keller GB (2017) Visuomotor Coupling Shapes the Functional Development of Mouse Visual Cortex. Cell, 169, 1291-1302.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.023 Keller GB, Bonhoeffer T, Hübener M (2012) Sensorimotor mismatch signals in primary visual cortex of the behaving mouse. Neuron, 74, 809–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.040 Mahringer D, Zmarz P, Okuno H, Bito H, Keller GB (2022) Functional correlates of immediate early gene expression in mouse visual cortex. bioRxiv, 2020.11.12.379909, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.12.379909 Meyer AF, Poort J, O’Keefe J, Sahani M, Linden JF (2018) A Head-Mounted Camera System Integrates Detailed Behavioral Monitoring with Multichannel Electrophysiology in Freely Moving Mice. Neuron, 100, 46-60.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.020 Niell CM, Stryker MP (2010) Modulation of Visual Responses by Behavioral State in Mouse Visual Cortex. Neuron, 65, 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.033 Saleem AB, Ayaz A, Jeffery KJ, Harris KD, Carandini M (2013) Integration of visual motion and locomotion in mouse visual cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 16, 1864–1869. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3567 Vélez-Fort M, Bracey EF, Keshavarzi S, Rousseau CV, Cossell L, Lenzi SC, Strom M, Margrie TW (2018) A Circuit for Integration of Head- and Visual-Motion Signals in Layer 6 of Mouse Primary Visual Cortex. Neuron, 98, 179-191.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.02.023 Wang KH, Majewska A, Schummers J, Farley B, Hu C, Sur M, Tonegawa S (2006) In Vivo Two-Photon Imaging Reveals a Role of Arc in Enhancing Orientation Specificity in Visual Cortex. Cell, 126, 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.038 Widmer FC, O’Toole SM, Keller GB (2022) NMDA receptors in visual cortex are necessary for normal visuomotor integration and skill learning. eLife, 11, e71476. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.71476 Xie H, Liu Y, Zhu Y, Ding X, Yang Y, Guan J-S (2014) In vivo imaging of immediate early gene expression reveals layer-specific memory traces in the mammalian brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 2788–2793. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1316808111 Yamada Y, Hada Y, Imamura K, Mataga N, Watanabe Y, Yamamoto M (1999) Differential expression of immediate-early genes, c-fos and zif268, in the visual cortex of young rats: effects of a noradrenergic neurotoxin on their expression. Neuroscience, 92, 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00003-2 | Functional correlates of immediate early gene expression in mouse visual cortex | David Mahringer, Pawel Zmarz, Hiroyuki Okuno, Haruhiko Bito, Georg B. Keller | <p>During visual development, response properties of layer 2/3 neurons in visual cortex are shaped by experience. Both visual and visuomotor experience are necessary to coordinate the integration of bottom-up visual input and top-down motor-relate... |  | Systems/Circuit Neuroscience | Julia Jade Harris | Anonymous, Petr Znamenskiy | 2021-12-14 20:30:39 | View |

03 Jul 2023

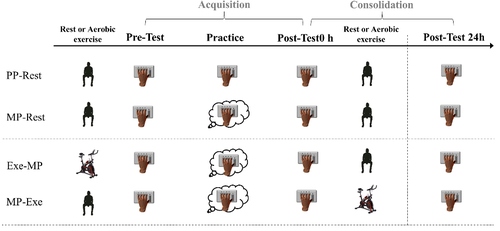

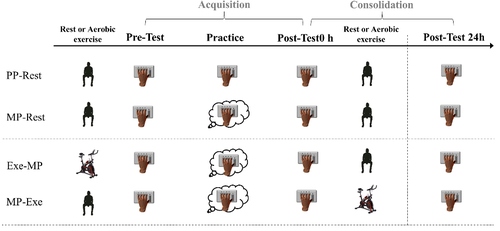

Optimizing the Benefits of Mental Practice on Motor Acquisition and Consolidation with Moderate-Intensity ExerciseDylan Rannaud Monany, Florent Lebon, Charalambos Papaxanthis https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.12.516269Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise augments motor consolidation after mental practice coupled with motor imageryRecommended by Damir Zubac based on reviews by Thibaut Sesia and 2 anonymous reviewersThis manuscript [1] describes the effects of aerobic exercise on the mental (or cognitive) performance of young healthy volunteers. The authors report that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (after mental practice) further enhanced performance during motor consolidation, at least at the level of the PP-rest group. Because an increase in performance was observed, the possibility of transferring these results to sports and rehabilitation is reasonable, as also suggested by similar work in this field [2]. This work is of great interest to researchers and sports practitioners interested in improving motor performance. The authors should also consider applying this model to clinical populations where the benefits of MP are more than welcome. Nevertheless, further studies should provide better insight into exercise intensity domains, individual oxygen uptake, muscle activation patterns, etc. Overall, the authors have responded to and implemented the reviewers' comments and suggestions well. 1. Monany DR, Lebon F, Charalambos P (2023). Optimizing the Benefits of Mental Practice on Motor Acquisition and Consolidation with Moderate-Intensity Exercise. bioRxiv, 2022.11.12.516269 ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.12.516269 2. Freitas, E., Saimpont, A., Blache, Y., & Debarnot U. (2020). Acquisition and consolidation of sequential footstep movements with physical and motor imagery practice. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(12), 2477-2484. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13799

| Optimizing the Benefits of Mental Practice on Motor Acquisition and Consolidation with Moderate-Intensity Exercise | Dylan Rannaud Monany, Florent Lebon, Charalambos Papaxanthis | <p>The optimization of mental practice (MP) protocols matters for sport and motor rehabilitation. In this study, we were interested in the benefits of moderate-intensity exercise in MP, given its positive effects on the acquisition and consolidati... |  | Behavioral/Cognitive Neuroscience | Damir Zubac | 2022-11-16 18:50:41 | View | |

02 Sep 2021

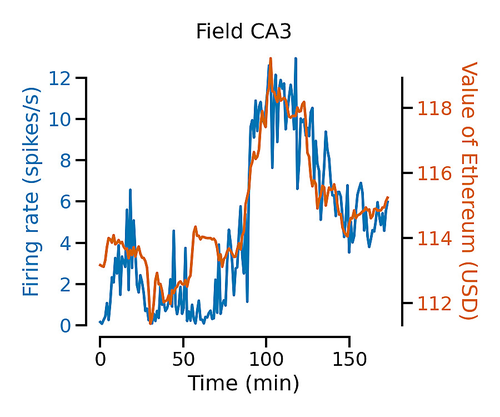

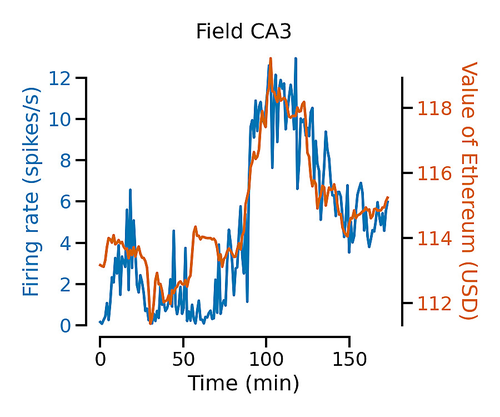

Neurons in the mouse brain correlate with cryptocurrency price: a cautionary taleGuido Meijer https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/fa4wzCan a mouse understand the crypto market?Recommended by Hernando Martinez Vergara based on reviews by Kenneth Harris, Anirudh Kulkarni and 1 anonymous reviewerNowadays it is pretty much accepted that in animals with a nervous system, neural activity leads to behaviour. This framework is very useful to ultimately find a satisfying explanation of how and why animals behave, as it implies that there is a causal relationship between neuronal spiking and muscle and gland activity. In order to get closer to this causation, a common approach in neuroscience is to find correlations between behavioural variables and neuronal activity. Dr. Meijer's manuscript "Neurons in the mouse brain correlate with cryptocurrency price: a cautionary tale" [1] serves as a proof of concept that neuroscientists need to be careful about the statistical tests they use when looking for these correlations. In this work, the author considers two recent datasets containing signals that display slow continuous trends over time: neuronal spiking activity from 40,100 neurons, and Bitcoin and Ethereum prices. When testing for correlations between the activity of individual neurons and the simultaneous fluctuations of cryptocurrency prices, he finds that over two thirds of the neurons correlated significantly, and that classical corrective conservative methods still result in one third of the neurons showing correlation. In order to estimate the true false discovery rate of these type of comparissons, the author tested two statistical methods shown to work for simulated data [2]. He shows that also for this large-scale dataset, both the session permutation and the linear shift method manage to reduce the number of correlated neurons to statistically-acceptable levels. Additionaly, the author goes on to show that it is the slow time constant of the crypto prices that are the root for the initial correlations. This work serves as an example for how mislead scientists can be if proper statistical tests are not applied in order to avoid "nonsense correlations" with neuronal data, and it aims to increase awareness about this problem in the neuroscience community. This rigorous and yet entertaining work can now be added to the collection of cautionary tales that include a dead salmon understanding human emotions [3] and rat cortical neurons predicting stock market prices [4]. At the very least, it can be a piece of advice for Elon Musk to wait for more evidence before merging two of his new recent interests. References [1] Meijer, Guido. (2021). Neurons in the Mouse Brain Correlate with Cryptocurrency Price: A Cautionary Tale. PsyArXiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Circuit Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/fa4wz. [2] K. D. Harris. (2020). Nonsense correlations in neuroscience. bioRxiv. 402719. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.29.402719 [3] http://prefrontal.org/files/posters/Bennett-Salmon-2009.jpg [4] T. Marzullo, C. Miller, and D. Kipke. (2016). Stock Market Behavior Predicted by Rat Neurons2. Annals of Improbable Research 12, 401. PDF Link | Neurons in the mouse brain correlate with cryptocurrency price: a cautionary tale | Guido Meijer | <p>In this paper I report the discovery of neurons which showed a neural correlate with ongoing fluctuations of Bitcoin and Ethereum prices at the time of the recording. I used the publicly available dataset of Neuropixel recordings by the Allen I... |  | Electrophysiology, Methods development | Hernando Martinez Vergara | 2021-06-08 14:19:54 | View | |

29 Nov 2021

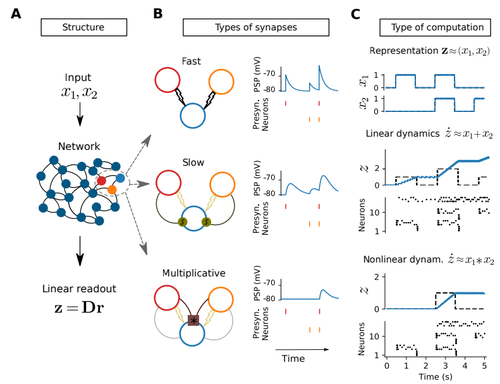

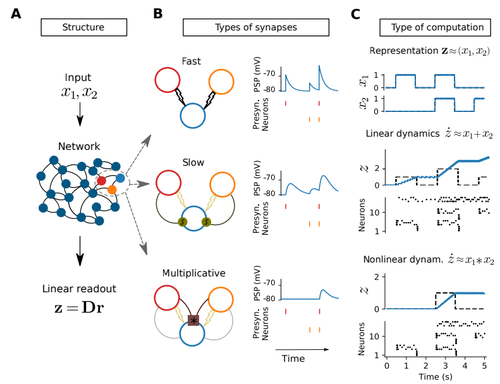

Nonlinear computations in spiking neural networks through multiplicative synapsesMichele Nardin, James W Phillips, William F Podlaski, Sander W Keemink https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.03857v4Approximate any nonlinear system with spiking artificial neural networks: no training requiredRecommended by Marco Leite based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersArtificial (spiking) neural networks (ANNs) have become an important tool in the modelling of biological neuronal circuits. However, they come with caveats: their typical training can be laborious, and after it is done, the complexity of the connectivity obtained can be almost as daunting as the original biological systems we are trying to model. In this work [1], Nardin and colleagues summarize and expand upon the Spike Coding Network (SCN) framework [2], which originally provides a direct method to derive the connectivity of a spiking ANN representing any given linear system. They generalize this framework to approximate any (non-linear) dynamical system, by yielding the connectivity necessary to represent its polynomial expansion. This is achieved by including multiplicative synapses in their network connections. They show that higher polynomial orders can be efficiently represented with hierarchical network structures. The resulting networks not only enjoy many of the desirable features of traditional ANNs, like robustness to (artificial) cell death and realistic patterns of activity, but also a much more interpretable connectivity. This is promptly leveraged to derive how densely connected a neural network of this type needs to be to be able to represent dynamical systems of different complexities. The derivations in this work are self-contained and the mathematically inclined neuroscientist can quickly get up to speed with the new multiplicative SCN framework, without the need for prior specific knowledge of SCNs. All the code is available and well commented in https://github.com/michnard/mult_synapses making this introduction even more accessible to its readers. This paper is relevant for those interested in neural representations of dynamical systems and the possible roles for multiplicative synapses and dendritic non-linearities. Those interested in neuromorphic computations will find here an efficient and direct way of representing non-linear dynamical systems (at least those well approximated by low-order polynomials). Finally, those interested in neural temporal pattern generators might find it surprising that only 10 integrate and fire neurons can already very reasonably approximate a chaotic Lorenz system.

[1] Nardin, M., Phillips, J. W., Podlaski, W. F., and Keemink, S. W. (2021) Nonlinear computations in spiking neural networks through multiplicative synapses. arXiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Neuroscience. https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.03857v4 [2] Boerlin, M., Machens, C. K., and Denève, S. (2013). Predictive coding of dynamical variables in | Nonlinear computations in spiking neural networks through multiplicative synapses | Michele Nardin, James W Phillips, William F Podlaski, Sander W Keemink | <p>The brain efficiently performs nonlinear computations through its intricate networks<br>of spiking neurons, but how this is done remains elusive. While nonlinear computations<br>can be implemented successfully in spiking neural networks, this r... |  | Synapse, Systems/Circuit Neuroscience | Marco Leite | 2021-04-07 17:38:49 | View | |

20 Apr 2021

A quick and easy way to estimate entropy and mutual information for neuroscienceMickael Zbili, Sylvain Rama https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.04.236174Estimating the entropy of neural data by saving them as a .png fileRecommended by Haudur Freyja Olafsdottir, Mahesh Karnani and Fleur Zeldenrust based on reviews by Federico Stella and 2 anonymous reviewers and Fleur Zeldenrust based on reviews by Federico Stella and 2 anonymous reviewers

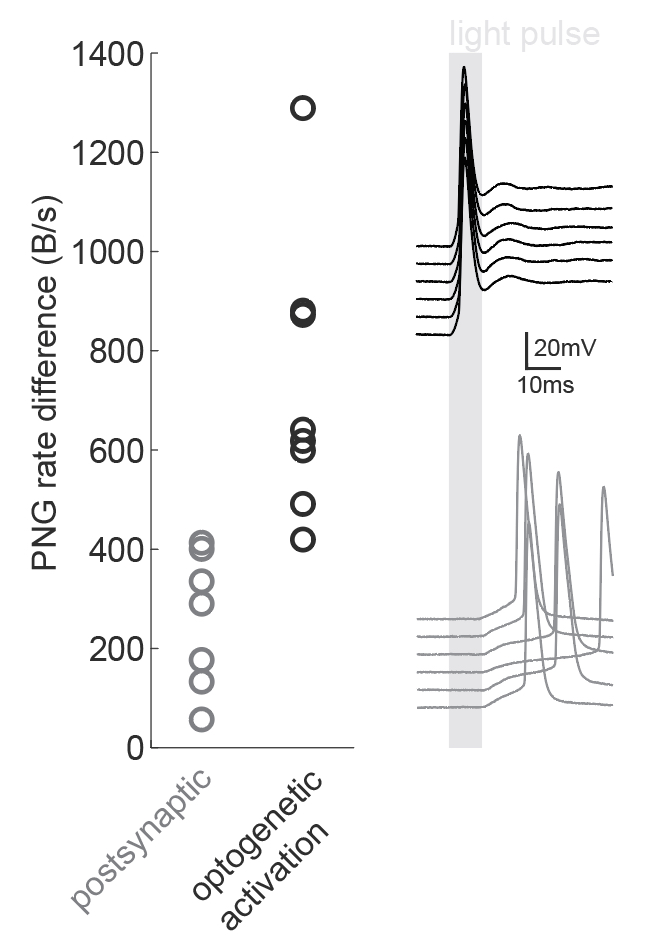

Entropy and mutual information are useful metrics for quantitative analyses of various signals across the sciences including neuroscience (Verdú, 2019). The information that a neuron transfers about a sensory stimulus is just one of many examples of this. However, estimating the entropy of neural data is often difficult due to limited sampling (Tovée et al., 1993; Treves and Panzeri, 1995). This manuscript overcomes this problem with a 'quick and dirty' trick: just save the corresponding plots as PNG files and measure the file sizes! The idea is that the size of the PNG file obtained by saving a particular set of data will reflect the amount of variability present in the data and will therefore provide an indirect estimation of the entropy content of the data.

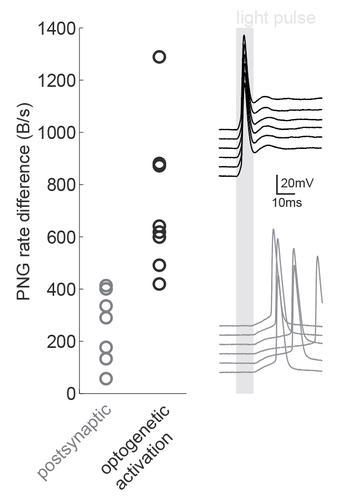

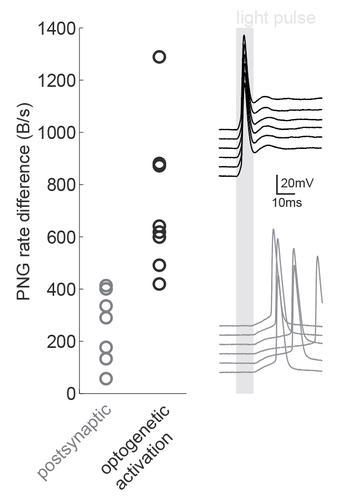

Figure caption: Using a PNG entropy metric to distinguish between direct optogenetic responses and postsynaptic excitatory responses. Left, PNG rate difference calculated for whole cell recordings of optogenetic activation in brain slices. About 20 consecutive 60ms sweeps were analysed from each of 7 postsynaptic cells and 8 directly activated cells. Analysis was performed as in Fig4B of the preprint (https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.04.236174) using code from https://github.com/Sylvain-Deposit/PNG-Entropy/blob/master/BatchSaveAsPNG.py. Right, six example traces from a cell carrying channelrhodopsin (black, top) and a cell that was excited synaptically (gray, bottom).

References Ince, R.A.A., Mazzoni, A., Petersen, R.S., and Panzeri, S. (2010). Open source tools for the information theoretic analysis of neural data. Front Neurosci 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.01.011.2010

| A quick and easy way to estimate entropy and mutual information for neuroscience | Mickael Zbili, Sylvain Rama | <p>Calculations of entropy of a signal or mutual information between two variables are valuable analytical tools in the field of neuroscience. They can be applied to all types of data, capture nonlinear interactions and are model independent. Yet ... |  | Electrophysiology | Haudur Freyja Olafsdottir | Federico Stella, Anonymous | 2020-08-06 13:36:25 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Amanda Almacellas Barbanoj

Ian Greenhouse

Rebecca Jordan

Mahesh Karnani

Florent Lebon

Vincent Magloire

Thibaut Sesia